the #befriending prayer of Ananias of Damascus

In various mindfulness approaches there are befriending or compassion meditations. These again have their roots in Buddhist tradition of metta or loving kindness meditations. These would include compassion for oneself, a stranger and even someone we find difficult.

Of course loving-kindness and compassion play a central part in Christianity as well. As I looked at these metta meditations I was struck by their similarity to the prayer of Ananias of Damascus for Saul of Tarsus.

In the Book of Acts in the New Testament in chapter nine Saul has his famous Damascus Road experience. He is on his way to Damascus to arrest followers of The Way (Christians) when he is arrested by the risen Lord Jesus Christ.

Temporarily blind Saul is led into Damascus. A man there called Ananias has a vision from God who asks him to go and pray a prayer of blessing on Saul which will restore his sight and fill him with the compassionate presence of God, the Holy Spirit.

Ananias questions the wisdom of praying for a stranger and an enemy, but God encourages him out of the way of fear into the way of love. It is clear that the prayer of Ananias has a significant impact on Saul. When Saul talks about his encounter with Jesus, which includes the prayer of Ananias when scales fell from his eyes, and he is filled with the Holy Spirit, he says he has had three important experiences.

‘Not that I have already obtained all this, or have already been made perfect, but I press on to take hold of that for which Christ Jesus took hold of me.’ (Philippians 3:12)

The word here for ‘took hold’ is literally ‘arrested.’ On the road to Damascus the love of Christ took hold of him.

When the scales fell from his eyes he ‘saw the light’. In 2 Corinthians 4:6 he says, ‘For God, who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness,’ made his light shine in our hearts to give us the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ.’ This reference to light shining out of darkness goes back to Genesis 1:3 where God said ‘Let there be light.’

So Saul was taken hold of by the love of Christ, and the light of the love of God shone in his heart.

He then says in 1 Timothy 1:13-14, ‘Even though I was once a blasphemer and a persecutor and a violent man, I was shown mercy because I acted in ignorance and unbelief. The grace of our Lord was poured out on me abundantly, along with the faith and love that are in Christ Jesus.’

The compassionate mercy, grace and love of God were poured into Paul like an overwhelming river.

I felt in part these experiences were because of Ananias’ prayer of befriending and compassion. So I have put them in prayer form that we can pray first for ourselves, then a stranger, then an enemy, and finally back for ourselves. In the words of one of Jesus’ most important statements ‘Love your neighbour as yourself’ (Matthew 22:39).

These are the prayers:

May the love of Christ take hold of me

May the light of Christ shine in my heart

May the love of Christ flow through me like a river

and then

May the love of Christ take hold of him/her

May the light of Christ shine in his/her heart

May the love of Christ flow through him/her like a river

We pray it for our own self, then a stranger, then an enemy and finally for our own self again. Change is laid down by a succession of fresh experiences of love. In our prayer of blessing and befriending something real happens.

the ego – a concretization of God-forgetfulness and a #mindful remedy

Dorothee Soelle has a beautiful phrase, ‘the ego is a concretization of God-forgetfulness.’ Not only that the ego is a concretization of other-forgetfulness, of creation-forgetfulness. We live in an ego-dominated world.

Whether it is what Manfred Kets de Vries calls the destructive egotism of narcissism characterized by ‘self-centredness, grandiosity, lack of empathy, exploitation, exaggerated self-love, and failure to acknowledge boundaries.’ (The Leader On The Couch, p. 25)

Or whether it is the ego-driven quest of the empty consumer self, seeking to fill its emptiness with ever more possessions that are completely unnecessary, and serve only to feed the ego.

About seven years ago when I was stressed and anxious a little book called ‘The Jesus Prayer’ by Simon Barrington Ward lept off the shelf at me. The Jesus Prayer, Lord Jesus Christ Son of God have mercy on me a sinner helps us learn to sustain and switch our capacity for attention, as well as become aware of the presence of God.

At the same time as practicing this prayer I was doing some counselling and psychotherapy training at Roehampton and came across mindfulness within psychology. I felt these two different strands were related.

I then started researching one of the pioneers of the Jesus Prayer, a 5th century Bishop Diadochus of Photike – and came across an idea of his about ‘mindfulness of God.’ That phrase range me like a bell and I have been fascinated with researching it ever since.

The Greek phrase Diadochus uses which was translated mindfulness of God was mneme theou, literally the memory of God, or the remembrance of God – a living memory. This of course is the antidote to the ego as concretisation of God-forgetfulness, other-forgetfulness and creation-forgetfulness.

The practice of the memory of God helps us to remember God, remember others, remember creation, and remember our true self – made in the image and likeness of God. It releases us from the prison of the ego into a new freedom.

charged moments in ordinary time and more in being #mindful

In the stillness and silence of Easter Saturday the green blade is rising, the moments that approach the resurrection are increasingly charged until God emerges in the resurrection of Jesus of Nazereth.

It seems that silence and stillness lead to charged moments at other times as well. Christina Feldman who teaches mindfulness says that people ‘practising Buddhist mindfulness are seeing liberation in bite-size pieces.’ (quoted in ‘Mindfulness in Schools’ a dissertation by Richard Burnett, p. 23).

Terence Handley MacMath in her article in the Church Times recently writes about her experience of attending a secular mindfulness-based stress-reduction course (MBSR), and says ‘for many it became a revelation of what I would call a spiritual way of life.’ (Church Times, 22nd March 2013, p. 17)

I heard someone else say recently that meditation had led to deeper insights about reality.

In silence and stillness different insights emerge as we practice attention and awareness. Human attention and awareness are gifts from God. Meister Eckhart says this about gifts, ‘God never gives, nor did He ever give a gift, merely that man might have it and be content with it. No, all gifts which He ever gave in heaven or on earth, He gave with one sole purpose – to make one single gift: Himself.’ (quoted in The Silent Cry, Dorothee Soelle, p. 21) As Dorothee Soelle points out all gifts that are given point back to the Giver (p.21).

The gifts of attention and awareness point back to their Giver. This particular time, that stretches from Good Friday to Easter Sunday is a time to pay particular attention. It is the time that can stretch our awareness infinitely.

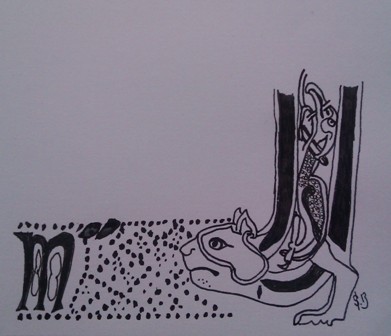

The Lindisfarne cat and the #mindless birds

A cat forms the right-hand margin of the initial Luke page of the Lindisfarne Gospels. It’s head faces the bottom line of text, apparently attentive towards the mass of inattentive birds on the other side of the page – of which it has already swallowed eight.

A little picture showing the importance of being attentive, and the perils of being inattentive; the importance of being mindful and the dangers of living mindlessly.

Elements of #mindfulness emerging in early Christian spirituality

Elements of mindfulness emerging in early Christian spirituality

A very rare bird from Africa, a Hoopoe was spotted by an attentive home owner in Poole recently, blown a thousand miles off course from its planned destination on the shores of the Mediterranean. It was amazing to see his photo, the last one I had seen used to land in our garden in Nairobi.

Also making the news each week is mindfulness, which some might categorize as an Eastern import blown thousands of miles off course, and not native to the West or Christianity.

However, if you look at the desert ascetics within early Christian spirituality you find elements of mindful awareness practice emerging, because mindfulness as an ability to be attentive and aware is a universal human capacity.

What are these elements?

The first is the self-regulation of attention, and in particular the ability to sustain one’s attention. This is called nepsis or watchfulness, ‘One should always stand guard at the door of one’s heart or mind..’[1]

This unceasing attentiveness is learnt through the use of the Jesus Prayer where we learn to switch our attention back to the repeated prayer and our breath when our mind wanders, ‘Lord Jesus Christ Son of God have mercy on me a sinner.’

This was all part of a consistent strategy, ‘nepsis (vigilance), watchfulness, the guarding of the heart (custodia cordis) and of the mind, prayer, especially the invocation of the name of Jesus, and so forth.’[2]

What the ascetic is guarding against is the afflictive thoughts. These early Christians developed a sophisticated psychology which mirrors that of modern cognitive psychologists.

The modern psychologists emphasise the importance of the mindful person avoiding elaborative and ruminative secondary processes in their mind. Rather than ‘getting caught up in ruminative, elaborative thought streams about one’s experience and its origins, implications, and associations, mindfulness involves a direct experience of events in the mind and body.’[3]

The early Christian ascetics differentiated between the first thought and secondary elaborative and ruminative processes:

‘There is the prosbole (suggestion in thought), which is free from blame…Next follows the syndiasmos (coupling), and inner dialogue with the suggestion (temptation), then pale or struggle against it, which may end with victory or with consent (synkatathesis), actual sin.’[4]

Through a process called exagoreusis ton logismon (revelation of thoughts) the beginning stage of the process of awareness/mindfulness is to catch the first thought before it moves into elaborative and secondary processes of thought, ‘One must crush the serpent’s head as soon as it appears.’[5]

Just as modern psychologists recognize that a thought, once it has been noticed, loses its power, so the early ascetics noticed the same thing, ‘As a serpent flees instantly as soon as it has left its hole, so an evil thought dissipates as soon as it begins to be disclosed.’[6]

Now, obviously before the thought can be disclosed to a spiritual father or mother, you need to become aware of it.[7] There was no experiential avoidance, each thought was rigourously named, each element of temptation recognized and labelled. As with any act of awareness of sustained attention it requires the ability to be aware in the present moment. There is no thought suppression, the first thoughts are disclosed to a spiritual elder immediately they are noticed. It is intentional and investigative. This mindfulness has an ethical and community dimension.

These terms – sustained attention, switching attention, self-regulation of attention, being in the present moment, elaborative and secondary processes, rumination, experiential avoidance, acceptance, intentional investigative awareness – are all terms and insights from the world of cognitive psychology.

They are also the first part of a proposed operational definition of mindfulness from a team of researchers.[8] Mindfulness as a mode of awareness that is a universal human capacity needs to be distinguished from the meditative, or mindful awareness practices, that evoke it.

Bishop et al. (2004) propose a two-component model of mindfulness: ‘

The first component involves the self-regulation of attention so that it is maintained on immediate experience, thereby allowing for increased recognition of mental events in the present moment.’[9]

Those of you familiar with mindfulness definitions will recognise the echoes of present-moment awareness, and paying attention to the streams of thoughts, feelings, ruminations, etc. within our minds.

The second component of their proposed operational definition involves adopting ‘a particular orientation towards one’s experiences in the present moment,’ which we will come back to.[10]

To continue our look at the self-regulation of attention, Bishop et al. (2004) point out the link to mindfulness. Mindfulness brings awareness ‘to current experience.’[11] What is required to maintain such an awareness are ‘skills in sustained attention.’[12]

One of the main meditative, or mindful awareness, practices is attending to your breath. This is a reality-focused, neutral practice that anyone can do. It is not religious or spiritual.

Attending to your breath develops your skills of sustained attention so that ‘thoughts, feelings, and sensations can be detected as they arise in the stream of consciousness.’[13] In mindful awareness practice the practitioner needs to ‘bring attention back to the breath once a thought, feeling or sensation has been acknowledged.’[14] This develops skills in switching attention which in turn makes our ability to be attentive more flexible.

There is another benefit to this self-regulation of attention. Bishop et al. (2004) conclude that the notion of mindfulness as a metacognitive process is implied in their operational definition because it involves monitoring and control.[15]

The monitoring element is important and involves a certain orientation to experience , including curiosity and acceptance. Acceptance is defined as ‘being experientially open to the reality of the present moment.’[16]

Acceptance is often misunderstood as passivity, but it is about ‘allowing’ current thoughts, feelings and sensations (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson)’.[17]

Acceptance can helpfully be seen as the opposite of thought-suppression or experiential avoidance; it is facing the reality of the thoughts, feelings and sensations we have.

As the authors argue ‘most forms of psychopathology involve, in some way or another, the intolerance of aspects of private experience, as well as patterns of experiential avoidance in an attempt to escape private experience’ (see Hayes et al., 1996, for evidence supporting this view.)[18]

A more skilful response to situations that provoke these more difficult feelings and thoughts can be cultivated through mindfulness.[19] With this orientation of curiosity and acceptance towards one’s experience, a further clarification of the definition of mindfulness can be put forth, as a ‘process of investigative awareness that involves observing the ever-changing flow of private experience.’[20]

This is an intentional effort because the client:

is instructed to make an effort to notice each object in the stream of consciousness (e.g., a feeling), to discriminate between different elements of experience (e.g., an emotional ‘feeling’ sensation from a physical ‘touch’ sensation) and observe how one experience gives rise to another (e.g., a feeling evoking a judgmental thought and then the judgemental thought heightening the unpleasantness of the feeling).[21]

This is worth quoting in full because it points out how much of this is acute observation of what actually goes on in our minds, usually out of our awareness and automatically.

This monitoring of the stream of consciousness is likely to correlate to increased emotional awareness and psychological mindedness.[22] Within this monitoring is the insight that we are not our thoughts and feelings, that these are passing events and not a direct readout of reality or necessarily inherent aspects of the self.[23]

The Desert Fathers and Mothers, and those who came after them also recognized thoughts as passing events, with some that were harder to deal with, ‘One should not ask questions about all the thoughts that are [in your mind];they are fleeting, but [ask] only about the ones that persist and wage war on man.’[24] Thoughts were also relativised, through recognizing they might have been prompted by demons, ‘One should always stand guard at the door of one’s heart or mind, and ask every suggestion that presents itself, ‘Are you one of ours, or from the opposing camp?’[25]

In summary, there are a number of things that can be said in this look at the first part of this proposed operational definition (Bishop et al., 2004)’s article. This is what they say:

we see mindfulness as a process of regulating attention in order to bring a quality of non-elaborative awareness to current experience and a quality of relating to one’s experience within an orientation of curiosity, experiential openness, and acceptance. We further see mindfulness as a process of gaining insight into the nature of one’s mind and the adoption of a de-centred perspective (Safran & Segal, 1990) on thoughts and feelings so that they can be experienced in terms of their subjectivity (versus their necessary validity) and transient nature (versus their permanence).[26]

They also summarise mindfulness as ‘a mode of awareness that is evoked when attention is regulated in the manner described.’[27] They argue that this mode, or psychological process, is only evoked and maintained whilst attention is being regulated in the manner they describe, with the open orientation to experience.[28]

There are fascinating parallels here between the proposed operational definition for mindfulness by cognitive psychologists outlined above, and the spirituality of the early Christian ascetics, which deserve to be explored further.

[1] Haussher, Irenee, (1990). Spiritual Direction in the Early Christian East (Cistercian Publications, p.225).

[2] Ibid, p.157.

[3] Teasdale, J.D., Segal, Z.V., Williams J.M.G., & Mark, G. (1995). How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behavior Research and Therapy, 33, 25-39, quoted in Bishop, S.R. et al. ‘Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition’ (2004). Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11 (232).

[4] Haussher, Irenee, (1990). Spiritual Direction in the Early Christian East (Cistercian Publications, p.157).

[5] Ibid, p.157.

[6] Ibid, p.157-158).

[7] Ibid, p.223.

[8] Bishop, S.R. et al. ‘Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition’ (2004). Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11 (230-241).

[9] Ibid, p. 232.

[10] Ibid, p.232.

[11] Ibid, p.232.

[12] Ibid, p.232.

[13] Ibid, p.232.

[14] Ibid, p.232.

[15] Bishop, S.R. et al. ‘Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition’ (2004). Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11 p.233.

[16] Roemer, L., & Orsillo, S.M. (2002), quoted in Bishop, S.R. et al. ‘Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition’ (2004). Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11 (233).

[17] Quoted in Bishop, S.R. et al. ‘Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition’ (2004). Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11 (233).

[18] Hayes, S.C., Wilson, K.G., Gifford, E.V., Follette, V.M. & Strosahl, K. (1996).’ Experiential avoidance and behavioural disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment’. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(6), 1152-1168. Quoted in Bishop, S.R. et al. ‘Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition’ (2004). Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11 (237).

[19] Bishop, S.R. et al. ‘Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition’ (2004). Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11 (235).

[20] Ibid, p.234.

[21] Ibid, p. 234.

[22] Ibid, p.234.

[23] Ibid, p.234.

[24] Barsanuphius quoted in Haussher, Irenee, (1990). Spiritual Direction in the Early Christian East (Cistercian Publications, pp.227-228).

[25] Ibid, p.225.

[26] Ibid, p.234.

[27] Ibid, p.234.

[28] Ibid, p.234.

Lent, men and resilience in the face of recession depression

Lent, men and resilience in the face of recession depression

We all like to play with sticky snow that makes snowballs, and lament wet snow that cannot hold together. Fuller Youth Institute has developed the theme of ‘sticky faith’ for young people. They’ve developed it because the church is losing young people when they leave, what has been referred to as, the goldfish bowl of church and are thrown into the open sea of the world. Their faith doesn’t stick.

Have you also noticed the lack of men in the church? According to some recent research, at the current rate of loss there will be no men in the church in this country by 2028.

An implicit concept in the idea of sticky faith is resilience, faith that sticks even in difficult circumstances. The government has been focusing on preventing suicide among young men, but new figures show a sharp increase in suicide among middle-aged men. This is partly about a lack of resilience in the face of life’s difficulties such as losing a job, financial worries, or a breakdown in relationships.

Psychologists are seeing a rise of what they call ‘recession depression,’ with a rise in depression, anxiety and suicide ideation due to financial hardship.

The youth specialists from Fuller Youth Institute argue that the way to make faith stick is to notice God through spiritual practices. I think there is a similar lack of ‘sticky faith’ among men, and the solution is the same. These spiritual practices practised regularly are a key way to develop resilient faith.

The 40 days of Lent (which means spring) is an opportunity for new growth in creating ‘sticky faith’. Forty days is a significant biblical number. It is also the length of time that helps us, psychologically, to break unhelpful habits and start new helpful ones. Making changes stick is not easy. It is why Lent as a season is so important. I first really discovered the power of Lent and 40 days when I read Rick Warren’s bestseller The Purpose Driven Life. Ever since then I have taken Lent seriously. It can change lives, with change that sticks.

By the way, do keep eating chocolate; Lent is about something else. It is a chance to notice Jesus again in a fresh way.

One of the problems with creating ‘sticky faith’ with men is that they are presented with a distorted, feminised portrait of Jesus. We need to rediscover a lost portrait of Jesus: he is not gentle Jesus, meek and mild; he does not float around in a nightgown. Mark’s gospel offers us a neglected title for Jesus, one that speaks powerfully to men. Jesus is called the ‘more powerful one’ by John the Baptist (Mark 1:7). In the Greek he is literally ‘the stronger one’.

Who does this make Jesus like? It echoes the portrayal of Yahweh as divine warrior in Isaiah’s new exodus theology.

So Jesus is the divine warrior. But he was also a contemplative. Men like the idea of being a warrior, but how do we get men to take contemplation seriously, because many don’t?

One ancient term for a contemplative is that of a ‘tracker’. The contemplative was someone who tracked ‘the footsteps of the Invisible One’, in the words of a fifth century Bishop, Diadochus of Photike. This is the lost bushcraft of the soul that men need to be reintroduced to if they are going to be changed into the likeness of Christ and develop his resilience. TV programmes by wilderness experts like Bear Grylls and Ray Mears are very popular with men.

Lent is associated with Jesus’ 40 days in the wilderness, where he battled Satan and contemplated God. It also echoes the story of the Exodus, the people of God in the wilderness journeying from slavery into freedom. Isaiah the prophet talked about a new exodus. As Christians we believe that is what Jesus came to fulfil, and Mark’s gospel takes up this theme.

Lent is also a time for recognising that in order for Jesus to do this, his journey needed to end with the cross and the resurrection. This process begins in Mark’s gospel with Jesus ‘the stronger one’ binding Satan ‘the strong one’(Mark 3:22-27) at the beginning of his ministry.

It is on the cross that he completes his eschatological victory over Satan, death and sin. That victory, won in principle, needs now to be won in reality in the present through hard conflict. Men who are caught in bitter existential battles with lust, greed, power and the slavery of the economic system – who are caught in addictions to pornography, alcohol, drugs and the emptiness of competing in the arena of consumerism – need to hear the language of the strong man being bound in their lives. This language needs to be part of their spiritual rebirth. Forty days of wrestling with these addictions this Lent might just be the breakthrough they need.

In my pastoral experience and in running a men’s group, and counselling men, helping them use the language of binding the strong man in their spiritual life is very important, as is asking them what is the strong man that needs binding. Which inner demon afflicts them the most, to use the language of the earliest Christian psychologists, the Desert Fathers? The afflictive thoughts they identified are still the ones that need wrestling with: gluttony, lust and greed; anger, sadness and spiritual apathy, or carelessness; vanity and pride.

We may have opened the door to Christ, but very often we fail to close the door to Satan; very often we fail to close the door on our sinful thought patterns. These thoughts are tracked and transformed through spiritual practices like Lectio Divina (a slow, prayerful tracking of God through reading Scripture in a meditative way)and the Jesus Prayer, the simple repetition with our breath of the ancient words, ‘Lord Jesus Christ Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner,’ which enables us to become aware of the presence of God. They also enable us to step back from the catastrophic thinking that can spin us into depression, anxiety or even suicidal thoughts, when we face redundancy or other difficulties, and help us to notice the small details of God still involved in our lives.

We need to go back to Scripture to recapture the true image of Jesus and men, and we need to go back to more ancient traditions than our own to challenge our thinking. Lent is a perfect opportunity to unplug from the things that drive us and consume us.

But just as we need to get our children to notice God more, and learn to pay attention to Him, so we need to do that with men. They need to be taught how to track God again, to relearn the joy, to borrow the words of a wilderness expert, of tracking the Mystery to its Source.

My talk at Somerville College Chapel Oxford, #mindfulness- a Christian perspective

My talk at Somerville College Chapel Oxford, #mindfulness- a Christian perspective

Link to my talk on ‘mindfulness – a Christian perspective’ at Somerville College Chapel Oxford, now on their blog

Better link to UCB radio interview with me on silence and contemplation

Better link to UCB radio interview with me on silence and contemplation

Link to UCB Christian radio Paul Hammond’s interview with me earlier this year on silence, contemplation, meditation and mindfulness

How can #mindfulness be secular, Buddhist, or Christian?

How can mindfulness be secular, Buddhist or Christian? Richard Burnett has written an excellent, well-researched, erudite and thought-provoking thesis called ‘Mindfulness in schools: learning lessons from the adults – secular and Buddhist (see link below). Within his thesis are important ideas that enable us to begin to answer the question above.

Firstly, mindfulness can be used in different settings because it is a universal human capacity for awareness and attention in the present-moment and must be distinguished from the meditative or mindful awareness practices that lead to this mode of awareness. In an important note on page 6 of his thesis Burnett says, ‘There is nothing ‘Buddhist’ about being mindful and paying attention to the present moment. Kabat-Zinn compares this to calling gravity ‘British’ because it was discovered by Newton.’

Secondly, it has a historical presence in Buddhism and Christianity, and in secular psychology there has also been a long focus on awareness and attention and the regulation of emotions. In other words people came across the capacity for mindfulness within different contexts, originally these contexts were religious. The other key idea, then, is to understand the context.

Richard Burnett is someone who has looked at this question of context within the setting of introducing mindfulness into schools (http://mindfulnessinschools.org/).

Thirdly, in counselling there is an important emphasis on client autonomy, respecting a person’s world view, experience and ethical values. That means boundaries are important. What is the context in which the client lives? An atheist might want to engage with a purely secular mindfulness.

This question of boundaries and client autonomy arises in mindfulness because it is a universal human capacity, and therefore appears in different contexts. These forms must be well defined and clearly articulated, although there is shared territory between the forms as well as distinctives. But a secular mindfulness course must not be ‘Buddhism by the back door.’ (p.32)

The key question is I guess: how do we ensure secular mindfulness is secular, Buddhist mindfulness is Buddhist and Christian mindfulness is Christian, for those to whom it matters? Someone looking at life through a secular lens for example.

Burnett argues, quite rightly that mindfulness in schools does not have the same objective as clinical psychology, because ‘in a classroom context we are not treating specific pathologies.’ (p. 24). Nor can it be introduced as a spiritual practice ‘as a classroom is not the place for religious instruction.’ (p.24) It can be used more generally to promote the key attitudes found in the National Framework for religious education of ‘self-awareness, respect for all, open-mindedness and appreciation and wonder.’ (p.27)

It then requires what has been called an ‘informational context’ (Feldman); or a ‘framework of understanding’ (Teasdale) or what Kabat-Zinn calls ‘scaffolding’. (p.28) Buddhist mindfulness is set within an ancient and complex scaffolding. (p.28) Helpfully, Burnettt argues that ‘The scaffolding in clinical mindfulness may be much smaller, but is very well constructed and arguably more effective in the treatment of specific conditions.’ (p.29) Mindfulness within Buddhism is set within religious or spiritual scaffolding, within clinical mindfulness it is secular (generally), although there are psychologists reframing Buddhism as a wise and ancient psychology and bringing in Buddhist insights that are psychological.

Burnett quotes from Kabat-Zinn, the pioneer of clinical mindfulness, as saying that mindfulness ‘may have to give up being Buddhism in any formal religious sense.’ (p.31)

This clear boundary around clinical mindfulness to ensure it is secular is important as Burnett outlines in a quote from Michael Chaskalson, (one of the key figures in mindfulness he has interviewed): ‘If you don’t establish clear boundaries you will exclude some people. There will be practising Christians for example, or dedicated Dawkins style atheists coming on courses and I don’t want to exclude them from conversation.’ (p.31)

So within schools Burnett argues that mindfulness should not be Buddhist (almost certainly). (p.31) If you are doing a Religious Studies A-level in Buddhism you would refer to the Buddhist scaffolding. But when taught as a practice it should be within scaffolding that is clearly secular. In that context what it can address, as a backbone for the engagement, is what Mark Williams calls ‘universal vulnerabilities.’ Although specific vulnerabilities identified in the context of schools such as ‘anxiety of exams,’ peer pressure, or mood swings, could be indicated to pupils. (p.33)

Burnett argues that mindfulness, especially in schools, brings with it ‘a sense of possibility.’ ( p.33). Burnett highlights these other possibilities, pointing out that there are a broad ‘range of potential applications’, including functional, therapeutic, to more spiritual applications when the context is appropriate. (p.33)

What I have been trying to develop, through ‘A Book of Sparks: a Study in Christian MindFullness’ and other writings, is a Christian scaffolding, drawing on biblical and historical roots for the development of mindfulness within the Christian tradition, as well as looking at the benefits of engaging with it today.

Within this setting I believe it has spiritual as well as therapeutic benefits, because of the overlaps, and shared territory, and because we are ’embodied’ people. The evidence-based research within clinical psychology suggests that it would also be appropriate to point Christians, under the holistic guidance of doctors and therapists, to secular clinical mindfulness which might address ‘specific’ vulnerabilities they might be living with. For Christians are not immune from the universal and specific vulnerabilities that afflict all human beings.

Within this research I am keen to work collaboratively with other Christians who are interested in mindfulness, both psychologically and theologically. I am grateful for the collaborative partnerships that are beginning. Space doesn’t permit a description of the scaffolding that makes mindfulness Christian, I have done that elsewhere, but I do believe that for Christians, as well, as they rediscover their contemplative roots, it has a very real ‘sense of possibility.’